EXPOSICOES

o que ja passou por aqui

anjo de fogo e A turma: a pintura como máscara

por Outra turma

Eu sou como o vento que varre a cidade

Você me conhece e não pode me ver

Presente de grego, Cavalo de Troia

Eu sou cobra jiboia e saci-pererê

Um anjo caolho que olhou os dois lados

Dormiu no presente, sonhou no passado

Olhou pro futuro, me disse que não, não!

Anjo de Fogo, Alceu Valença

Sinistros brincantes cortam a paisagem e o mormaço. Sob o sol a pino animam sombras com suas vestes franjadas. Por trás de máscaras feitas de pêlo de bode – ou de látex, daquelas com cara de cachorro, caveira, bruxa ou diabo –, atazanam a população, ao som de bandas cabaçais, crianças e motos. É a turma dos caretas. (Ou, dependendo da região, a turma dos papangus). Chegam zanzando como uma gangue em frenesi, loucos num espetáculo enredado de beleza e paixão, violência e galhofa, em pleno feriado santo.

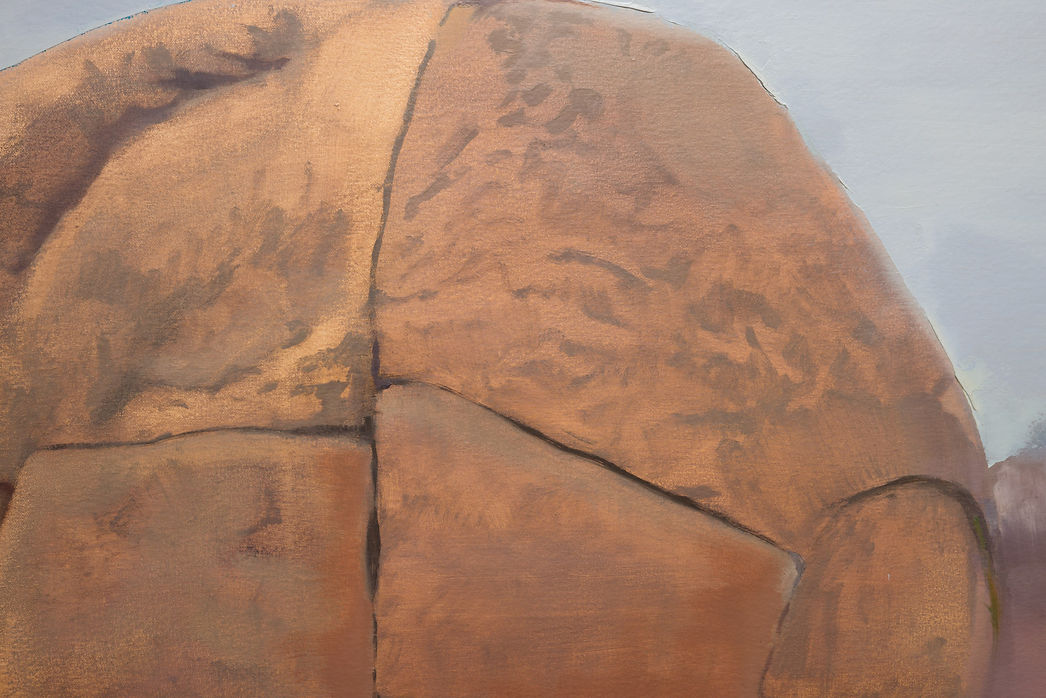

Em algum lugar desse mesmo chão repousa um monólito. Não, melhor: em algum lugar desse mesmo chão repousa uma estrutura colossal de concreto, que olha para cima em um estado quase meditativo, aterrado pelo seu peso. É a cabeça de um santo, oca, com ar de santuário, uma casca de cimento, ferro e fé, que parece resguardar segredos e preces sussurradas diante de copos submersos. Sublime anedota do realismo mágico cearense, a moleira do Santo Degolado é a história real de uma obra nunca terminada, uma estátua de Santo Antônio que ficou para trás. Aqui, A Cabeça do Santo [1] mais parece uma bola de fogo. O anjo de fogo.

O conjunto de trabalhos apresentados nessa exposição costura um encontro cordelístico entre entidades e territórios.Artur Bombonato sutura as histórias com um olhar estrangeiro familiar. Cidadão instigado, Bombonato já foi encarado e arrebatado por estas cenas, visitou a cabeça do santo e sentiu a presença dos caretas arrepiar os pelos da nuca.

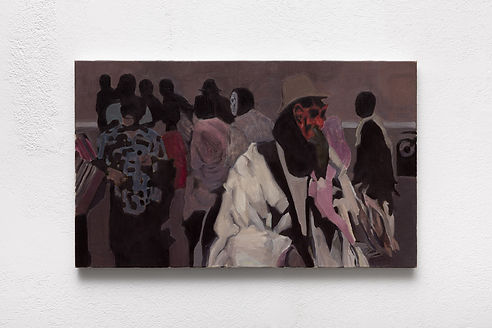

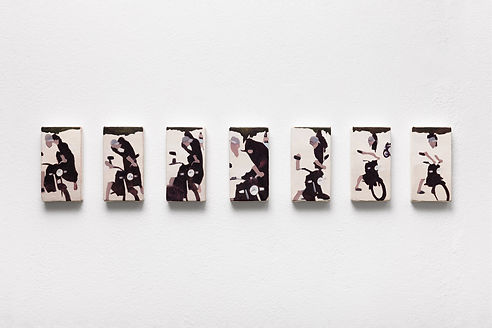

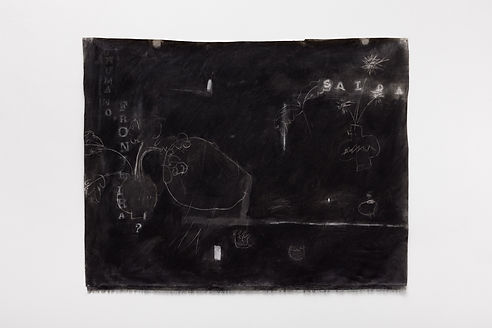

O artista cearense expande então esse universo através de horas e horas de pesquisa na internet, colhendo e fuçando entre vídeos amadores em busca de cantos e motivos perdidos nesses registros. A metodologia é um constante visitar, interromper, intrometer-se no material alheio, numa construção imagética que aglutina memória, fragmentos narrativos e profunda investigação pictórica. Assim, os eventos vão sendo (re)profanados pelas mídias em todo o processo, resultando em imagens cheias de fugacidade e movimento, como que vistas de canto de olho.

Com espacialidade pronunciada, as pinturas denunciam um trabalho meticuloso de escala, cor e forma. De perto, esse esforço também mostra-se marcado pela quantidade de camadas e detalhes, que indicam uma negociação constante com os erros e recomeços, inquietação de quem não se contenta com uma beleza nascida da fluidez, mas que, ao contrário, só se convence na peleja com o plano, do tal ajustamento de impurezas [2] que é a pintura. Bombonato faz e desfaz, mancha e desmancha. Lava, raspa, joga fora se for preciso, coloca a perder.

O diabo – obsessão do artista – mora nos detalhes. Não só como figura, mas como a linha que arremata tema e método, as entidades e a forma de fazer pintura. Se ele é um simulacro de impureza, fortuidade, esforço mundano e morte, também o é do prazer, do desejo e das gargalhadas noite adentro. Ou ainda, diabo pode ser só um nome para o que é difícil de nomear: aquele momento em que algo se presentifica, se ativa, agora sem retorno, a exaustão do esforço final subindo como calor ao pé da orelha, a falha se fazendo concretude. A máscara está pronta.

Notas

[1] Socorro Acioli, A Cabeça do Santo

[2] Philip Guston, Philip Guston’s Poem-pictures

anjo de fogo and A Turma: painting as mask

by Outra turma

I am like the wind that sweeps through the city

You know me, but you cannot see me

A gift from the Greeks, Trojan Horse

I am a boa constrictor and Saci-Pererê

A one-eyed angel who looked at both sides

Slept in the present, dreamed in the past

Looked at the future, told me no, no!

Anjo de Fogo, Alceu Valença

Sinister revelers cut through the landscape and the heat. Under the blazing sun, they animate shadows with their fringed garments. Behind masks made of goat hair – or latex ones, resembling dogs, skulls, witches, or devils – they harass the population to the sound of cabaçal bands, children, and motorcycles. They are the group of caretas (or, depending on the region, papangus). They arrive staggering like a gang in a frenzy, wild in a spectacle tangled with beauty and passion, violence and mockery, on a holy holiday.

Somewhere on this very ground lies a monolith. No, better: somewhere on this very ground lies a colossal concrete structure, looking up in an almost meditative state, weighed down by its mass. It’s the head of a saint, hollow, with the air of a sanctuary, a shell of cement, iron, and faith, which seems to guard secrets and whispered prayers before submerged glasses. A sublime anecdote of Ceará's magical realism, the skull of the Santo Degolado (Beheaded Saint) is the true story of an unfinished work, a statue of Saint Anthony that was left behind. Here, A Cabeça do Santo (The Head of the Saint) [1] looks more like a ball of fire. The angel of fire.

The body of work presented in this exhibition weaves a cordel-like encounter between entities and territories. Artur Bombonato sutures stories with a familiar foreign gaze. An intrigued citizen, Bombonato has already been faced with and captivated by these scenes, visited the head of the saint, and felt the presence of the caretas (masked revelers) sending chills down his neck.

The Ceará-born artist expands this universe through hours and hours of internet research, collecting and sifting through amateur videos in search of songs and motifs lost in these recordings. His methodology is a constant visiting, interrupting, and meddling with others' material, in an imagistic construction that gathers memory, narrative fragments, and deep pictorial investigation. In this way, the events are (re)profaned by the media throughout the process, resulting in images full of fleetingness and movement, as if seen from the corner of the eye.

With pronounced spatiality, the paintings reveal a meticulous work of scale, color, and form. Up close, this effort also shows itself marked by the number of layers and details, indicating a constant negotiation with mistakes and re-beginnings, the restlessness of one who is not content with beauty born of fluidity, but who, on the contrary, only convinces himself in the struggle with the canvas, in the adjustment of impurities [2] that is painting. Bombonato makes and unmakes, stains and unravels. He washes, scrapes, throws it away if necessary, lets it go to waste.

The devil – the artist’s obsession – resides in the details. Not only as a figure, but also as the line that ties together theme and method, entities and the act of painting itself. If he is a simulacrum of impurity, happenstance, mundane effort, and death, he is also one of pleasure, desire, and laughter late into the night. Or perhaps, the devil could just be a name for what is difficult to name: that moment when something presents itself, becomes active, now irreversible, the exhaustion of final effort rising like heat to the ear, the flaw becoming concreteness. The mask is

ready.

Notes

[1] Socorro Acioli, A Cabeça do Santo

[2] Philip Guston, Philip Guston’s Poem-pictures.

.png)

EXPOSICOES

o que ja passou por aqui

Gesto e algazarra

por Davi Almeida

Um mundaréu de gente segue em uma única direção. A pista se enche; todos ao redor são convidados para o cortejo do absurdo. O ser civil se ausenta para dar espaço a uma entidade coletiva que se expressa incendiando frustrações, cólera e júbilo como um caboclo em festa, na redentora energia da fuleragem.Em Anjo de Fogo e a Turma, primeira exposição individual de Artur Bombonato em São Paulo, vemos as consequências dessas sortes lançadas.

Artur olha para o abalo e o maravilhamento que as imagens da balbúrdia, dos cortejos populares e do carnaval de rua instigaram em seu imaginário desde a infância. Suas pinturas são povoadas de figuras vultuosas espalhadas em bando, sujeitos encaixados em enquadramentos que sugerem uma captura furtiva — o olhar de quem está lá no meio, vendo com os próprios olhos a turba. A vibração das massas de tinta remexidas desenha a amplitude desse grande rito dos alvoroços.

Os personagens de sua turma parecem se mover agitadamente; suas cores se misturam na paleta, borrando a veste de festa com o rastro do movimento, enquanto a luz parece vir de um sol neon, cintilante como serpentina. Manchas transparentes, fugidias e melancólicas, avizinhadas a cargas de cores fluorescentes, realçam a natureza desse evento transubstancial que carrega consigo uma verdade que a pintura está acostumada a sustentar: tudo é e não é, tudo é dois. A pintura, tecido plano coberto de tinta, é também um convite à crença no que se vê. Vestir a máscara é incorporar, negociar o real. Tudo é muito sério na brincadeira de troca de pele.

No dia do juízo da vizinhança, quando todos são convidados a lançar mão da trégua das desavenças para duelar no bailado de uma marcha que todos cantam juntos, o vira-lata late para o transeunte, a morte abraça e beija o cabra na moto, e o diabo parece dar o ar da graça por diversas vezes no rosto alheio, como um maestro do desmantelo geral.

E no quarteirão de cima, uma cabeça de santo tomba na calçada, como que exaurida por uma fadiga imensa, arregando os ombros da imagem que, no topo da serra, ouve as preces dos fiéis da cidade. Essa cabeça que dorme talvez defina para mim o que Bombonato apreendeu em pintura: que tudo o que é real é fruto dos sonhos vividos dos santos que repousam em nossos quintais.

Gesture and Uproar

By David Almeida

A massive crowd moves in a single direction. The street overflows; everyone around is swept into a parade of the absurd. The

individual gives way to a collective force that expresses itself by setting frustrations, rage, and joy ablaze—like a reveler in sacred frenzy, driven by the redemptive energy of mischief.

In Anjo de Fogo e a Turma (Angel of Fire and the Gang), Artur Bombonato’s first solo exhibition in São Paulo, we see the consequences of these fates thrown to the wind.

Artur reflects on the emotional impact and wonder stirred in him since childhood by the images of chaos, grassroots parades, and street carnival. His paintings are inhabited by towering figures moving in clusters, characters caught in frames that feel like candid captures—like the gaze of someone deep in the crowd, witnessing the madness firsthand. The thick, swirling paint marks trace the vastness of this great rite of disorder.

His gang of characters seem to move wildly; their colors blend together on the palette, smearing festive costumes with the traces of motion, while the light seems to emanate from a neon sun, glittering like party streamers. Transparent, fleeting, melancholic smudges sit beside bursts of fluorescent color, revealing the nature of this shape-shifting event—carrying a truth that painting has long known how to hold: everything is and isn’t, everything is doubled. A painting, flat fabric layered with pigment, is also an invitation to believe in what you see. Wearing the mask is to become, to negotiate with reality. In the playful ritual of shedding one’s skin, everything becomes deadly serious.

On the neighborhood’s day of reckoning, when everyone is called to lay down their quarrels and join the swirling march sung in unison, the stray dog barks at the passerby, death embraces and kisses the man on the motorcycle, and the devil seems to make multiple cameo appearances—smiling through the faces of strangers like the conductor of total chaos.

And on the block uphill, the head of a saint lies toppled on the sidewalk, as if drained by immense fatigue, bowing the shoulders of the statue that, from the mountaintop, listens to the city’s faithful prayers. That sleeping head may very well define what Bombonato captures in his painting: that everything real is born from the lived dreams of the saints resting in our backyards.

.png)

pentimento

Ana Takenaka

Daniel Mello

Gabriel Torggler

EXPOSICOES

o que ja passou por aqui

Pintura soterrada

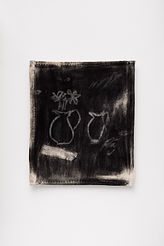

O termo italiano pentimento refere-se aos arrependimentos que surgem ao longo do processo artístico. Visível ou não, esse procedimento está especificamente relacionado ao campo da pintura, quando uma imagem é apagada e coberta por outra. Embora seja facilmente reconhecível na figuração, o conceito se torna nebuloso no contexto do abstracionismo. Nesse caso, o que está soterrado pode ser tanto um arrependimento quanto uma nova composição.

As obras de Ana Takenaka, Daniel Mello e Gabriel Torggler, reunidas nesta exposição, oferecem um panorama da produção recente de cada artista, todos interessados em explorar a tela como um espaço de investigação de seus materiais e técnicas de preferência. Em comum, encontramos superfícies soterradas por camadas de pigmento, de onde emergem figuras ou sugestões de imagens que revelam a atração do trio por interpretações abertas e insinuações narrativas.

Ana Takenaka tem feito do carvão o protagonista de sua obra. A partir do atrito entre o material e a superfície rugosa da tela, a artista deposita grandes quantidades desse mineral e, depois, como quem escava o solo, constrói imagens que nos remetem a artefatos, hieróglifos, silhuetas e outros símbolos associados à antiguidade. Em um remix entre memória e História, Takenaka utiliza a característica polvorosa do carvão para criar composições de aspecto enevoado, onde tudo parece vestígio, pronto para desaparecer a qualquer momento.

Por sua vez, Daniel Mello explora a fisicalidade do óleo em forma de bastão para criar pinturas densas, nas quais campos cromáticos entram em embate. É importante destacar que o próprio artista fabrica o óleo que utiliza, o que resulta em um material preparado para alcançar os efeitos desejados – que são muitos. Sua pintura é espessa, cheia de acúmulos, deixando à mostra as marcas da fisicalidade sobre a tela e nos outros objetos nos quais o material é aplicado. Das diversas formas possíveis de se observar um quadro, Mello tende a induzir o olhar ao ritmo das suas marcas sobre o suporte, frequentemente explorando os contrastes que surgem da sobreposição de uma paleta sobre a outra.

A tríade de artistas é complementada pela produção de Gabriel Torggler. Exímio desenhista, Torggler tem desenvolvido, há mais de uma década, uma obra que transita entre a psicodelia e uma estética saturada de cores e figuras. As obras que compõem essa exposição, no entanto, nascem das experimentações do pintor com a tinta automotiva, que lhe permite explorar uma infinidade de nuances, intensidades e transparências proporcionadas pelo uso do spray. Utilizada principalmente no fundo de suas composições, a tinta automotiva se contrasta com figuras em repetição, de formas indefinidas, construídas por meio de máscaras preenchidas por acrílica ou óleo. Essas imagens são reminiscências de suas pinturas anteriores, o que contribui para o senso de unidade de sua obra, que agora se afirma em uma nova etapa.

Embora distintas em seus materiais e abordagens, as três produções compartilham uma vontade comum, evidenciada pelo procedimento de soterramento que dá origem a novas formas, camadas e significados. Nelas, o ato de ocultar e revelar nos faz refletir sobre os processos de criação, arrependimento e destruição que permeiam o fazer artístico, mirando as ambíguas relações entre o visível e o invisível, o intencional e o acidental.

Post Scriptum:

Certa vez, perguntei a um pintor abstrato como ele sabia que uma pintura estava finalmente terminada. Ele respondeu: "É como fazer um bolo, você sabe quando está assado.".

Buried Painting

The Italian term pentimento refers to the regrets that emerge throughout the artistic process. Whether visible or not, this procedure is specifically linked to the field of painting, when one image is erased and covered by another. While it is easily recognizable in figurative work, the concept becomes elusive in the context of abstraction. In this case, what is buried can be either a regret or a new composition.

The works of Ana Takenaka, Daniel Mello, and Gabriel Torggler, gathered in this exhibition, offer an overview of each artist's recent production, all of whom are interested in exploring the canvas as a space for investigating their preferred materials and techniques. What they have in common are surfaces buried under layers of pigment, from which figures or suggestions of images emerge, revealing the trio’s attraction to open interpretations and narrative insinuations.

Ana Takenaka has made charcoal the protagonist of her work. Through the friction between the material and the rough surface of the canvas, the artist deposits large amounts of this mineral and then, as though digging the earth, she constructs images that remind us of artifacts, hieroglyphs, silhouettes, and other symbols associated with antiquity. In a remix between memory and history, Takenaka uses the dusty characteristic of charcoal to create compositions with a foggy appearance, where everything seems like a trace, ready to disappear at any moment.

Daniel Mello, in turn, explores the physicality of oil in stick form to create dense paintings, where chromatic fields clash. It’s important to note that the artist makes the oil he uses, resulting in a material prepared to achieve the desired effects — of which there are many. His paintings are thick, full of accumulations, exposing the marks of the material's physicality on the canvas and other objects it is applied to. Among the various ways of observing a painting, Mello tends to guide the viewer's gaze to the rhythm of his marks on the surface, often exploring contrasts that arise from the layering of one palette over another.

The trio of artists is complemented by the work of Gabriel Torggler. An excellent draftsman, Torggler has been developing work for over a decade that straddles psychedelia and an aesthetic saturated with colors and figures. The works in this exhibition, however, are born from the painter’s experiments with automotive paint, which allows him to explore a myriad of nuances, intensities, and transparencies provided by the use of spray. Primarily used in the background of his compositions, automotive paint contrasts with repeating figures of undefined shapes, constructed through masks filled with acrylic or oil. These images are reminiscences of his previous paintings, contributing to the sense of unity in his work, which now enters a new stage.

Although distinct in their materials and approaches, the three productions share a common will, evidenced by the procedure of burial that gives rise to new forms, layers, and meanings. In them, the act of concealing and revealing makes us reflect on the processes of creation, regret, and destruction that permeate artistic making, highlighting the ambiguous relationships between the visible and the invisible, the intentional and the accidental.

Post Scriptum: Once, I asked an abstract painter how he knew when a painting was finally finished. He replied: "It’s like baking a cake, you knowwhen it’s done."

Thierry Freitas

April 2025