EXPOSICOES

o que ja passou por aqui

Cidade Dorme

17 Novembro de 1986, oito horas da noite. Dimitry Davidoff, estudante da Universidade Estadual de Moscou, sobe as escadas do terceiro andar do departamento de psicologia. Na sala страшный seis outros alunos o aguardam sentados em uma mesa redonda. É quase inverno na Rússia, a União Soviética vai acabar cinco anos depois, mas algo naquela noite se propagaria perpetuamente entre eles e nós: a invenção do jogo Cidade Dorme, inicialmente conhecido como “Lobisomem”.

Inventada no contexto soviético da “cortina de ferro”, a brincadeira chegou a se tornar ferramenta de treinamento para os serviços de segurança russos, campeonato mundial em Las Vegas, série de televisão na Letônia e título de exposição de arte contemporânea no Brasil. A ideia para essa mostra surgiu durante uma rodada com alguns dos artistas, na ocasião falávamos sobre o terror em seu registro parodiado.

A paródia é um recurso recorrente nas práticas de artistas atuais e no próprio regime contemporâneo de produção de informação. De memes à deepfakes, o ato de se apropriar de um elemento original produzindo um deslocamento cômico, irônico ou exagerado é estratégia cotidiana nos veículos de comunicação. Nos filmes de terror, esse recurso é mobilizado através de certa comicidade. Seja através de um efeito de “comic relief” ou na adição de textura aos elementos do horror, o humor é frequentemente acionado dentro do gênero enquanto dispositivo de sátira e paródia, o que permite afastar o terror de um simples maniqueísmo entre bem e mal e localizar em seu enredo identificações familiares.

Não à toa, são objetos que remetem à brincadeira e ao jogo como bonecas, máscaras e tabuleiros que se revelam protagonistas de acontecimentos apavorantes em clássicos filmes de terror. Essa ambivalência fundamental entre o risível e o terrível foi explicitada em um acontecimento recente na mídia nacional. Quando grandes plataformas anunciavam a morte de Silvio Santos, o SBT transmitia Scooby-Doo. A referência não é gratuita, o filme de 2002, “Scooby-Doo; Ilha do Espanto”, foi crucial para a estrutura dessa exposição. Nele, a

Escola de Mistérios volta à ativa numa missão de terror tropical que se passa em um parque temático.

Próximo ao que propõe o filme, buscamos aqui também frequentar tal brecha da paródia, e propor a dúvida: por que o pavor faz rir? Nesse espaço estreito e constante, trabalhos em diferentes suportes mobilizam uma crise dos clichês sobre o terror medonho e destrutivo para afirmá-lo enquanto campo de construção de curiosidade, mistérios e fantasias compartilhadas que se proliferam em silêncio enquanto a cidade dorme.

Regras:

Um grupo de cinco ou mais pessoas deve formar uma roda. Reunidos, eles agora são integrantes de uma pequena cidade onde uma série de assassinatos tem se desenrolado. Inicialmente, deve-se chegar a um consenso sobre quem é Deus. Munido de seu poder supremo, Deus então passa a nos dizer quem somos e o que faremos utilizando apenas sua mão e voz abençoadas. Deus faz nossos olhos cerrarem pelo peso das pálpebras ao proferir as palavras “Cidade Dorme”.

Agora em que só há breu e escuridão, Deus passa a mão sob a cabeça de um participante e diz: assassino. Deus repete seus gestos distribuindo os outros personagens da trama: Anjo, Detetive e Povo. A partir de então dia e noite são comandados por sua maravilhosa e perfeita vontade, e nossos olhos são coreografados por seus dizeres. Quando anoitece, Deus acorda o assassino, que aponta sua vítima. Já de dia, antes de anunciar o morto, um Anjo pode tentar salvar um dos participantes através de um palpite. O sangue persiste até que o detetive finalmente chegue ao desfecho do mistério. Deus então troca de corpo para que o drama prossiga.

Lucas Alberto

The City Sleeps

November 17, 1986, eight o’clock in the evening. Dimitry Davidoff, a student at Moscow State University, climbs the stairs to the third floor of the psychology department. In room страшный, six other students wait, seated around a round table. Winter is near in Russia, and the Soviet Union will dissolve five years later—but something from that night will perpetuate itself across time: the invention of the game The City Sleeps, initially known as Mafia or Werewolf.

Conceived in the context of the Soviet “Iron Curtain,” the game would go on to be used as a training tool by Russian intelligence services, become the subject of a world championship in Las Vegas, a TV series in Latvia, and, now, the title of a contemporary art exhibition in Brazil. The idea for this show emerged during a game night played with some of the artists; we were talking about horror and its parodied representations.

Parody is a recurring device in the work of contemporary artists, and in the broader regime of information production today. From memes to deepfakes, the act of appropriating an original element and creating a comic, ironic, or exaggerated displacement is a daily strategy in media discourse. In horror films, this strategy appears through a kind of comic texture. Whether through “comic relief” or through adding absurdity to horror elements, humor is often deployed within the genre as a device of satire and parody, allowing horror to drift from a simple manichean frame of good versus evil toward stories with more familiar, even personal, identifications.

It’s no coincidence that playful objects—dolls, masks, board games—often become the protagonists of terrifying events in horror film classics. This fundamental ambivalence between the laughable and the terrifying was recently made explicit in a strange moment on Brazilian media: while major platforms announced the death of Silvio Santos, the TV channel SBT was airing Scooby-Doo. The reference is not arbitrary: the 2002 film Scooby-Doo: Spooky Island was central to the structuring of this exhibition. In the film, the Mystery Inc. gang is reunited in a tropical horror mission set on a theme park island.

As in the film, we too seek to occupy this slippage of parody and to ask: Why does terror make us laugh? Within this narrow, flickering space, the works in this exhibition—spanning various media—dismantle clichés of horror as a purely destructive or grotesque force, and instead affirm it as a field of curiosity, shared fantasy, and mystery that proliferates in silence while the city sleeps.

Rules:

A group of five or more people must form a circle. Together, they now make up a small town where a series of murders have taken place. First, the group must agree on who will be God. With divine power in hand, God begins to tell us who we are and what we will do, using only their voice and blessed hand.

God makes our eyelids heavy, commanding us to close our eyes by saying, “The City Sleeps.”

Now, in complete darkness, God touches the head of one participant and says: “Murderer.” God continues, assigning the other roles: Angel, Detective, and Townspeople.

From this point forward, day and night are orchestrated by God’s marvelous and perfect will, and our eyes move according to divine instructions.

At nightfall, the murderer awakens and points to their next victim. By daylight, before the dead are revealed, an Angel may attempt to save a life by guessing someone’s identity. The bloodshed continues until the Detective finally solves the mystery. God then reincarnates into another body, and the drama begins again.

Lucas Alberto

EXPOSICOES

o que ja passou por aqui

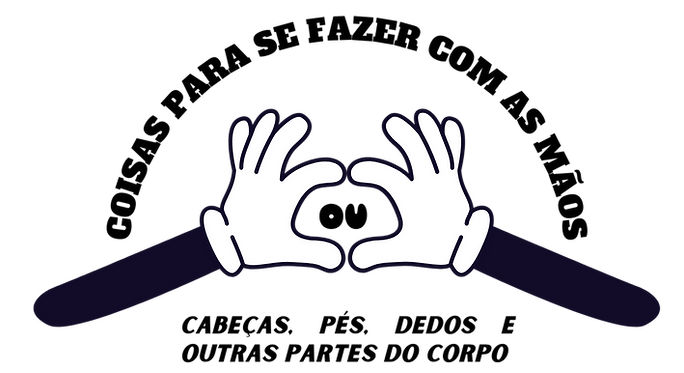

Coisas para se fazer com as maos - ou - cabecas, pes, dedos e outras partes do corpo

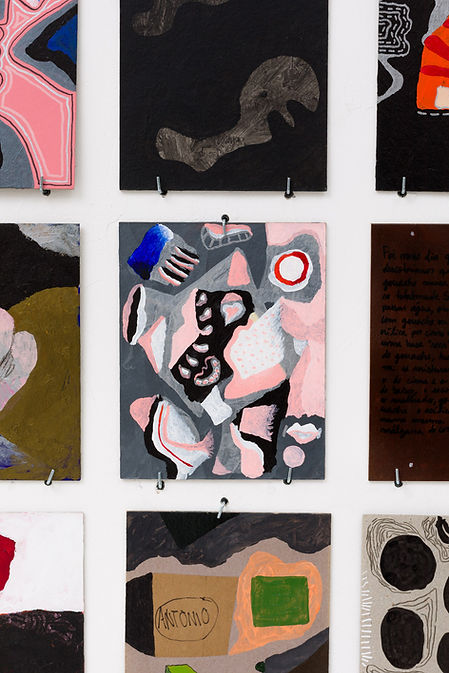

Os trabalhos de Antonio Malta Campos, Flavushh, Marcelo Cipis e Raquel Campos se encontram na medida em que se constroem na melodia da rotina e dos gestos. Aqui, os ícones dos artistas se tratam de sutilezas que podem passar despercebidas aos olhos acostumados. E não seriam essas sutilezas os verdadeiros grandes ícones?

Em Coisas para se Fazer com as Mãos ou Cabeças, Pés, Dedos e Outras Partes do Corpo, emblemáticos são os pés, os cochichos, o que fazer com as mãos enquanto se está sendo observado – e quanto pesam os cigarros e os copos em um evento social. Em Coisas para se Fazer com as Mãos ou Cabeças, Pés, Dedos e Outras Partes do Corpo, iconográficas são as banalidades comportamentais, o frio na barriga, a tensão, os pés tortos, os carimbos, as borboletas, os prédios, a fobia social e o grande assunto (ou o não assunto) que é tudo isso reunido.

As Misturinhas de Antonio Malta Campos (com colaboração da sua ex-assistente Antonia Baudouin) são uma espécie de despretensão que ganha forma através da experimentação. Assim como os desenhos de Flavushh, não há ensaio ou rascunho. As obras da artista estão finalizadas à medida que ela precisa pôr para fora o que digeriu do seu cotidiano, sem necessariamente prever o resultado final. Ambos os artistas têm seus trabalhos apresentados em painéis. Trabalhos individuais, mas que se entrelaçam e se complementam no todo e que falam por si.

Já os trabalhos de Cipis e Raquel trazem corpos distorcidos ou fragmentados. Gestuais e ações que ganham forma a partir da interpretação dos artistas das cores, formas e texturas. As pinturas de Cipis têm um quê de suprematismo, com formas e cores chapadas, enquanto as de Raquel se desdobram em composições de figura e fundo com nuances e pinceladas expostas com um quê de expressionismo.

A exposição não se encerra em si mesma. Os trabalhos dos quatro artistas não se encerram em si mesmos. Estão em constante construção, à medida que cada espectador interpreta as formas e figuras com seu próprio olhar. É sempre isso – ou algo mais. As obras transitam entre figurativo e abstrato, formam dicotomias, digressões, transgressões que dançam por entre as cores e formas diversas, mas que também se encontram por essas mesmas dicotomias e digressões, que passam a ser um canal de comunicação entre os artistas. Canal utilizado aqui, justamente, para falar sobre coisas para se fazer com as mãos, ou sobre pés, ou sobre mãos e pernas ou ainda outras partes do corpo. A justificativa da mostra está em si mesma, ou não há nenhuma.

Entre contrapontos e complementos, artistas de diferentes gerações trazem suas visões particulares do mundo. Em uma dança ritmada pela melodia do cotidiano, a subjetividade dos artistas confere ao banal contornos abstratos e distorções de cores e formas, criando assim, emblemáticas figuras do real ou crônicas visuais do ordinário.

Ana Gallo

Things to Do with Hands – or – Heads, Feet, Fingers, and Other Parts of the Body

The works of Antonio Malta Campos, Flavushh, Marcelo Cipis, and Raquel Campos converge in the melody of routine and gesture. Here, the artists’ icons reside in subtleties—those that may go unnoticed by eyes grown too accustomed. And are not these subtleties the true great icons?

In Things to Do with Hands – or – Heads, Feet, Fingers, and Other Parts of the Body, what is emblematic are the feet, the whispers, the idle positioning of hands when being observed—and the invisible weight of cigarettes and glasses at a social event. In this exhibition, iconography is found in behavioral banalities: butterflies in the stomach, social tension, twisted feet, stamps, butterflies (again), buildings, social phobia, and the big topic (or non-topic) that is the gathering of all these things.

Antonio Malta Campos’ Misturinhas (with the collaboration of his former assistant Antonia Baudouin) embody a kind of intentional unpretentiousness that takes shape through experimentation. Much like the drawings of Flavushh, there is no rehearsal, no sketch. Her works are finished the moment she needs to externalize what she has digested from everyday life, without necessarily anticipating the final outcome. Both artists present their work in panels—individual works that interlace and complement one another as a whole, speaking for themselves.

Cipis and Raquel’s works, on the other hand, portray distorted or fragmented bodies. Gestures and actions take form through the artists’ interpretation of color, shape, and texture. Cipis’s paintings carry a touch of Suprematism, with flat forms and bold colors, while Raquel’s unfold in figure-ground compositions marked by nuance and exposed brushstrokes reminiscent of Expressionism.

The exhibition doesn’t close in on itself. The works of these four artists remain open—always in construction, shaped anew by the eyes of each viewer. It is always this—or something else. The pieces move between figuration and abstraction, forming dichotomies, digressions, transgressions that dance across diverse colors and shapes. But these same digressions also serve to bring the works together, creating a channel of communication among the artists. That channel is used here precisely to speak of things to do with the hands, or the feet, or the legs, or yet other parts of the body. The justification for the exhibition lies within itself—or perhaps, nowhere at all.

Between contrast and complement, artists from different generations bring forth their particular visions of the world. In a dance attuned to the rhythm of the everyday, their subjectivities cast the banal in abstract contours and color-distorted forms—thus creating emblematic figures of the real, or visual chronicles of the ordinary.

Ana Gallo

EXPOSICOES

o que ja passou por aqui

Namoradeira: Marina Sader

No descompasso do kamikaze, nos encontramos e prometemos voltar, não mais em companhia de amigas, mas com amores. Engolimos nuvens de algodão doce, mordemos maçãs do amor e nos perdemos nos brilhos cintilantes da roda gigante. O cheiro de cigarro evoca noites longíquas, de sexo casual, vinho barato e tapetes macios. Existe algo visceral nas montanhas-russas; talvez, por isso, convidem a brincar com as emoções, explorando o apelo do efêmero e do

intenso.

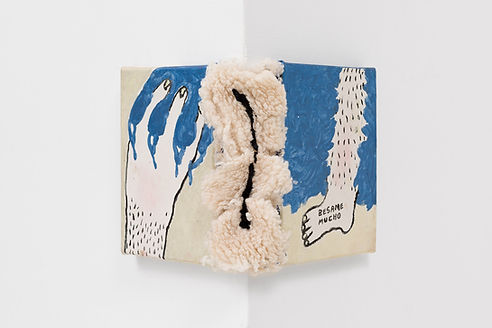

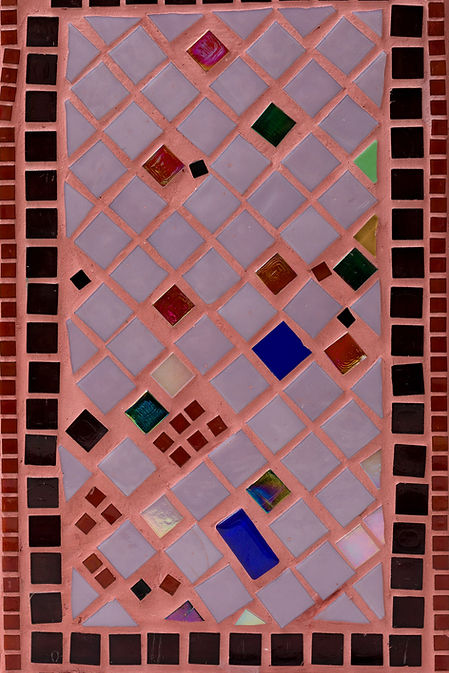

No Parque Marina, cacos de vidro tornam-se lentes e janelas, filtrando reminiscências e ilusões do público. Azulejos traçam o caminho de uma dança estratégica, onde pisar no tabuleiro faz parte da sedução. Cartas se tornam bilhetes e depois, playlists. Dos lábios, sorridentes e dormentes, escapam os sussurros de nossas provocações.

Aqui, não dizemos "estou enamorado de ti"; seguimos outros rituais: paquerar, amassar, pegar, ficar e estar ficando. O tempo verbal dita a intensidade da jogada. As cobertas desordenam o toque dos olhares e as faíscas da carne desmancham o esmero que sequer passa pela mente.

Não importa se o flerte nasceu no aconchego de um assento ou se revelou em uma janela; namoradeira é lugar e atitude. Deslizar sob a luz dos lençóis pode soar mal nas bocas alheias, mas carrega o tom de uma sabedoria que cura nossas dinâmicas sociais. Seja com dois, três ou quatro, saber se divertir é privilégio de quem desfruta e saboreia a si mesma.

Marina Schiesari

Flirt Bench: Marina Sader

In the offbeat rhythm of the kamikaze, we found each other and promised to return—not in the company of girlfriends this time, but with lovers. We swallowed clouds of cotton candy, bit into candy apples, and got lost in the shimmering lights of the Ferris wheel. The smell of cigarettes evokes distant nights of casual sex, cheap wine, and soft carpets. There is something visceral about roller coasters—perhaps because they invite us to play with emotions, to explore the allure of the fleeting and the intense.

At Parque Marina, shards of glass become lenses and windows, filtering the public’s memories and illusions. Tiles trace the steps of a strategic dance, where stepping onto the board is part of seduction. Letters turn into notes, and then into playlists. From lips—smiling, numbed—escape the whispers of our provocations.

Here, we don’t say “I’m in love with you”; we follow other rituals: flirting, making out, hooking up, staying together, and being in a situationship. The verb tense dictates the intensity of the game. The blankets disorder the gaze’s touch, and the sparks of flesh unravel any refinement that wouldn’t have even crossed our minds.

It doesn’t matter if the flirtation began in the comfort of a seat or was revealed through a window—namoradeira is both place and attitude. Slipping beneath the sheets' light might sound improper to others, but it carries the tone of a wisdom that heals our social dynamics. Whether with two, three, or four—knowing how to have fun is a privilege of those who savor and enjoy themselves.

Marina Schiesari